John Malcolm (Loyalist)

John Malcolm | |

|---|---|

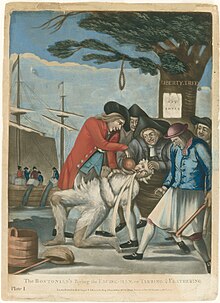

The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man, or, Tarring & Feathering, a 1774 British print, attributed to Philip Dawe,[1] combines assault on Malcolm with earlier Boston Tea Party in background. | |

| Born | May 20, 1723[2] |

| Died | November 23, 1788 (aged 65)[2] England |

| Occupation(s) | Customs official, army officer |

| Spouse | Sarah Balch (m.1750)[2] |

| Children | 5[2] |

| Family | Daniel Malcolm (brother) |

John Malcolm (May 20, 1723 - November 23, 1788) was an American-born customs official and army officer who was the victim of the most publicized tarring and feathering during the American Revolution.

Background

[edit]John Malcolm was from Boston and a staunch supporter of the Crown. During the War of the Regulation, he traveled to the Province of North Carolina to help put down the uprising. Working for the customs services, he pursued his duties with a zeal that made him very unpopular, as he was a Loyalist during the Tea Act. Malcolm faced numerous moments of abuse and provocation from Boston's Patriots, the critics of Crown authority. People often "hooted" at him in the streets, but Governor Thomas Hutchinson urged him not to respond.[3]

His unpopularity finally came to a boiling point in November 1773 when sailors in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, tarred and feathered him. However, during the process the sailors either had thoughts of pity or morality as they did not strip his clothes beforehand.[3] Two months later during his second ordeal Malcolm would not be as fortunate.

Incident in Boston

[edit]A confrontation with the Patriot shoemaker George Hewes thrust Malcolm into the spotlight. On January 25, 1774, according to the account in the Massachusetts Gazette, Hewes saw Malcolm threatening to strike a boy with his cane. When Hewes intervened to stop Malcolm, both men began arguing, and Malcolm insisted that Hewes should not interfere in the business of a gentleman. When Hewes replied that at least he had never been tarred and feathered himself, Malcolm struck Hewes hard on the forehead with the cane and knocked him unconscious.[4]

That night, a crowd seized Malcolm in his house and dragged him into King Street to punish him for the attack on Hewes and the boy. Some Patriot leaders who believed mob violence hurt their cause tried to dissuade the crowd by arguing that Malcolm should be turned over to the justice system. These pleas fell on deaf ears, however, as the relentless crowd justified the attack by citing Ebenezer Richardson amongst other grievances. Richardson was a customs official who had killed a 12-year-old Bostonian named Christopher Seider, but escaped punishment by receiving a royal pardon.[5]

Malcolm was stripped to the waist and covered with burning hot tar and feathers before he was forced into a waiting cart. The crowd took him to the Liberty Tree and told him to apologize for his behavior, renounce his customs commission, and curse King George III. When Malcolm refused, the crowd put a rope around his neck and threatened to hang him. That did not break him, but when they threatened to cut off his ears, Malcolm relented. The crowd then forced him to consume copious amounts of tea and sarcastically toasted the King and the royal family.[6] By this time Hewes (who had recovered) was so appalled by Malcolm's treatment that he attempted to cover him with his jacket.[7] Malcolm was finally freed and was sent home, but continued to endure physical beatings as he returned.[8]

Later life

[edit]On May 2, 1774, Malcolm moved to England where he hoped to secure compensation from the suffering he had endured in Boston.[2][7] Even though he submitted a petition for King George III, the king was already aware of his "famous case".[2] While awaiting a reply Malcolm unsuccessfully ran for Parliament against John Wilkes, the controversial champion of colonial rights.[9] Having received no reply through a messenger about his petition, on January 12, 1775 Malcolm himself "attended the levee at St. James’s, knelt before the King, and gave his petition into His Majesty's own hands."[2] Despite writing in his petition that he wanted to return to Boston and resume his duties as a customs official, and that being tarred and feathered was now a badge of honor for him, the king was not impressed.[2][7] Malcolm never returned to Boston for the remainder of his life due to the outbreak of the American Revolution. He was later given a commission as an ensign in 1780, for "an Independent Company of Invalids" at Plymouth, England. Malcolm died on November 23, 1788, leaving his widow in Boston to file a pension 21⁄2 years later.[2]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Fischer, Liberty and Freedom (Oxford University Press, 2005), 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcom". Massachusetts Colonial Society.

- ^ a b Young, Shoemaker, 47.

- ^ Young, Shoemaker, 48.

- ^ Young, Shoemaker, 49.

- ^ Letters of a Loyalist Lady : Being the Letters of Ann Hulton, Sister of Henry Hulton, Commissioner of Customs at Boston, 1767-1776. Cambridge, Mass. 1927. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-674-18348-3. OCLC 1165506697.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Nathaniel Philbrick (March 31, 2013). "The Worst Parade to Ever Hit the Streets of Boston". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Hoock, Holger (2017). Scars of independence : America's violent birth (First ed.). New York. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-8041-3728-7. OCLC 953617831.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Young, Shoemaker, 50

- Frequently cited sources

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8070-5405-4; ISBN 978-0-8070-5405-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Hersey, Frank W.C. "Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcom". Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 34 (1941): 429–73.